"It was Activision’s success that caused the crash. (...) In one 6 month period between CES shows, the number of Atari 2600 game publishers went from 3 to over 30. These were VC backed attempts to duplicate Activision’s success.

These companies failed to realize that making fun, compelling video games – particularly for the Atari 2600 – is massively difficult. They had no game designers, but instead hired programmers from other fields. These companies all failed, but not until they had built 1-2 million copies of the worst games you can imagine.

Those awful games flooded the market at huge discounts, and ruined the video game business."

David Crane, cofounder of Activision, interviewed in 2016

These companies failed to realize that making fun, compelling video games – particularly for the Atari 2600 – is massively difficult. They had no game designers, but instead hired programmers from other fields. These companies all failed, but not until they had built 1-2 million copies of the worst games you can imagine.

Those awful games flooded the market at huge discounts, and ruined the video game business."

David Crane, cofounder of Activision, interviewed in 2016

I asked GPT4 to give me a table of the top 20 highest-paying Hollywood actors to date in terms of cumulative career pay, measured in 2021 US dollars. I also asked it to append to the table the most profitable movie the actor was involved in; in case the actor was involved in a series of movies (say, for instance, as a character in the Marvel Cinematic Universe), then GPT4 was to just provide the name of the franchise the actor was involved in. The unedited output of that request can be found below.

Figure 1. Top 20 highest-earning actors in Hollywood history, according to GPT4.

Several interesting things come out of looking at this table.

First, all names are of actors that are still very active – even accounting for inflation, stars of Hollywood olden days like Humphrey Bogart, Elizabeth Taylor, Marlon Brando, Marilyn Monroe or Charlton Heston are nowhere to be seen.

Second, it’s clear that most actors in the list draw the bulk of their financial success from movie series. 5 of the 20 names have MCU as their most profitable endeavor; Fast & Furious and Harry Potter each supply 2 names to the list. Only 3 names (Leonardo DiCaprio, Sandra Bullock, and Angelina Jolie) don’t have a movie series as their main source of financial success.

Third, we also don’t see actors that participated in blockbuster franchises from before the 2000s – Harrison Ford (Star Wars, Indiana Jones), Mark Hamill (Star Wars), Sylvester Stallone (Rocky, Rambo), Arnold Schwarzenegger (Terminator) or Sigourney Weaver (Alien) come to mind. This happens even as they are mostly still active; it just happens to be that they are too old to re-star in their franchises in the same capacity as before.

The conclusion of all this is that something happened in Hollywood in the past 20 years that led to a strategic shift in how movies were made: the main studios decided they would focus on creating series of movies instead of single scripts, and also decided they could, and should, pay more for top talent.

First, all names are of actors that are still very active – even accounting for inflation, stars of Hollywood olden days like Humphrey Bogart, Elizabeth Taylor, Marlon Brando, Marilyn Monroe or Charlton Heston are nowhere to be seen.

Second, it’s clear that most actors in the list draw the bulk of their financial success from movie series. 5 of the 20 names have MCU as their most profitable endeavor; Fast & Furious and Harry Potter each supply 2 names to the list. Only 3 names (Leonardo DiCaprio, Sandra Bullock, and Angelina Jolie) don’t have a movie series as their main source of financial success.

Third, we also don’t see actors that participated in blockbuster franchises from before the 2000s – Harrison Ford (Star Wars, Indiana Jones), Mark Hamill (Star Wars), Sylvester Stallone (Rocky, Rambo), Arnold Schwarzenegger (Terminator) or Sigourney Weaver (Alien) come to mind. This happens even as they are mostly still active; it just happens to be that they are too old to re-star in their franchises in the same capacity as before.

The conclusion of all this is that something happened in Hollywood in the past 20 years that led to a strategic shift in how movies were made: the main studios decided they would focus on creating series of movies instead of single scripts, and also decided they could, and should, pay more for top talent.

Why talent inflation makes sense in Hollywood, and what AI has to do with it

In her great book “Blockbusters: Hit-making, Risk-taking, and the Big Business of Entertainment”, Harvard Business School professor Anita Elberse explains why. In the book, she argues that the strategy of betting on a few big-budget, high-profile projects rather than spreading resources across many smaller projects is the most effective way for companies to succeed in the entertainment industry. Established movie series help reduce the risk of those bets, since their past installments validate public interest in the story; and in exactly the same way, and for mostly the same reasons, so does established talent.

(Financially speaking, professor Elberse’s argument is that concentrated bets on established stars/franchises offer the highest potential of risk-adjusted returns in an industry where revenues are distributed according to power laws. Crucially, her argument holds true for any industry where success follows a power law – venture capital investing, for instance –, but that’s way out of scope of this text.)

In key ways, the top-earning talent in the list has become an integral part of the content produced by the movie studios. Think about it: Robert Downey Jr. is Tony Stark, Johnny Depp is Jack Sparrow, Hugh Jackman is Wolverine, Emma Watson is Hermione, and so on. But it’s also obviously true that they are all extremely charismatic individuals, with scores of fans, huge followings on social media, extremely popular names in podcasts or late night shows, etc. The best-paying actors possess both (a) a big role as a popular character, and (b) a captivating social presence.

We may be entering a world where both (a) and (b) can be achieved by an AI agent.

Next step: dystopia, democratization of content creation, or both

Let me illustrate what I mean by a silly example. Imagine, if you will, that Chris Hemsworth sells to Disney the perpetual right to use his personal image and voice for the character Thor, so that Disney could digitally use “Chris Hemsworth’s Thor” in any way the company would see fit. Since there is a lot of overlap between Chris Hemsworth and Thor, however, Chris Hemsworth also agrees to allow Disney to create an AI doppelganger of himself.

As such, imagine now that Disney creates an autonomous AI agent (see AutoGPT or BabyAGI) and tasks it with impersonating “Chris Hemsworth as Thor” to the best extent possible, maintaining an engaging online/social media presence and keeping itself true to any new material that Chris Hemsworth may do. Imagine now that Disney lets this AI agent interact with the studio as it’s creating a new Thor story, including by reading and criticizing the script, and evaluating its own performance in the CGI/Stable Diffusion-created scenes where Thor shows up; also, Disney lets the AI agent have authentically human responses – for instance, by letting it have and keep opinions that diverge from the studio’s editorial decisions, and even by voicing those differences in social media from time to time.

Fans would see two different “Chris Hemsworths” – the real one that exists in flesh and bone, and another one that exists in the digital metaverse, never ages, and exists only to star in Thor movies and to engage with his fans. We are not there yet, but with GPT4 + plug-ins + AutoGPT + generative art, we already possess a blueprint to doing something like this. It’s only a matter of time – and judging by the speed of progress in AI, ‘time’ here may mean a few months until a first attempt. Going further, AI agents could be created to assume animated characters like Tom Hanks’ Woody from Toy Story, or even be created from scratch as untethered to any individuals in real life, starring brand new franchises of their own.

This is heady stuff and we are surely moving into Black Mirror territory; I’m not getting into that beyond what I just described. Whether good or bad, we’re talking about a blueprint for infinite, automated content generation with close to zero marginal costs, and substituting actors for AI agents is just one of several hypothetical examples of that process.

But, again, we are not that far ahead yet. What’s most relevant to me is what is already true: thanks to generative art and large language models, we are living in a world where anyone can produce content, at a rate faster than the speed of thought, and with basically zero marginal cost. If you don’t believe me, just see this amazing video from Corridor Crew and judge for yourself. Generative AI is democratizing creative capacity at a scale the world has never seen before.

We’ve only really been in this world for the past month or so. What happens next?

Two lessons from the video game industry

The video game industry offers us two great stories that help us evaluate what could happen to content generation industries in a world where the main barriers to content creation are suddenly lifted. One is a cautionary tale; the other, a virtuous story.

In her great book “Blockbusters: Hit-making, Risk-taking, and the Big Business of Entertainment”, Harvard Business School professor Anita Elberse explains why. In the book, she argues that the strategy of betting on a few big-budget, high-profile projects rather than spreading resources across many smaller projects is the most effective way for companies to succeed in the entertainment industry. Established movie series help reduce the risk of those bets, since their past installments validate public interest in the story; and in exactly the same way, and for mostly the same reasons, so does established talent.

(Financially speaking, professor Elberse’s argument is that concentrated bets on established stars/franchises offer the highest potential of risk-adjusted returns in an industry where revenues are distributed according to power laws. Crucially, her argument holds true for any industry where success follows a power law – venture capital investing, for instance –, but that’s way out of scope of this text.)

In key ways, the top-earning talent in the list has become an integral part of the content produced by the movie studios. Think about it: Robert Downey Jr. is Tony Stark, Johnny Depp is Jack Sparrow, Hugh Jackman is Wolverine, Emma Watson is Hermione, and so on. But it’s also obviously true that they are all extremely charismatic individuals, with scores of fans, huge followings on social media, extremely popular names in podcasts or late night shows, etc. The best-paying actors possess both (a) a big role as a popular character, and (b) a captivating social presence.

We may be entering a world where both (a) and (b) can be achieved by an AI agent.

Next step: dystopia, democratization of content creation, or both

Let me illustrate what I mean by a silly example. Imagine, if you will, that Chris Hemsworth sells to Disney the perpetual right to use his personal image and voice for the character Thor, so that Disney could digitally use “Chris Hemsworth’s Thor” in any way the company would see fit. Since there is a lot of overlap between Chris Hemsworth and Thor, however, Chris Hemsworth also agrees to allow Disney to create an AI doppelganger of himself.

As such, imagine now that Disney creates an autonomous AI agent (see AutoGPT or BabyAGI) and tasks it with impersonating “Chris Hemsworth as Thor” to the best extent possible, maintaining an engaging online/social media presence and keeping itself true to any new material that Chris Hemsworth may do. Imagine now that Disney lets this AI agent interact with the studio as it’s creating a new Thor story, including by reading and criticizing the script, and evaluating its own performance in the CGI/Stable Diffusion-created scenes where Thor shows up; also, Disney lets the AI agent have authentically human responses – for instance, by letting it have and keep opinions that diverge from the studio’s editorial decisions, and even by voicing those differences in social media from time to time.

Fans would see two different “Chris Hemsworths” – the real one that exists in flesh and bone, and another one that exists in the digital metaverse, never ages, and exists only to star in Thor movies and to engage with his fans. We are not there yet, but with GPT4 + plug-ins + AutoGPT + generative art, we already possess a blueprint to doing something like this. It’s only a matter of time – and judging by the speed of progress in AI, ‘time’ here may mean a few months until a first attempt. Going further, AI agents could be created to assume animated characters like Tom Hanks’ Woody from Toy Story, or even be created from scratch as untethered to any individuals in real life, starring brand new franchises of their own.

This is heady stuff and we are surely moving into Black Mirror territory; I’m not getting into that beyond what I just described. Whether good or bad, we’re talking about a blueprint for infinite, automated content generation with close to zero marginal costs, and substituting actors for AI agents is just one of several hypothetical examples of that process.

But, again, we are not that far ahead yet. What’s most relevant to me is what is already true: thanks to generative art and large language models, we are living in a world where anyone can produce content, at a rate faster than the speed of thought, and with basically zero marginal cost. If you don’t believe me, just see this amazing video from Corridor Crew and judge for yourself. Generative AI is democratizing creative capacity at a scale the world has never seen before.

We’ve only really been in this world for the past month or so. What happens next?

Two lessons from the video game industry

The video game industry offers us two great stories that help us evaluate what could happen to content generation industries in a world where the main barriers to content creation are suddenly lifted. One is a cautionary tale; the other, a virtuous story.

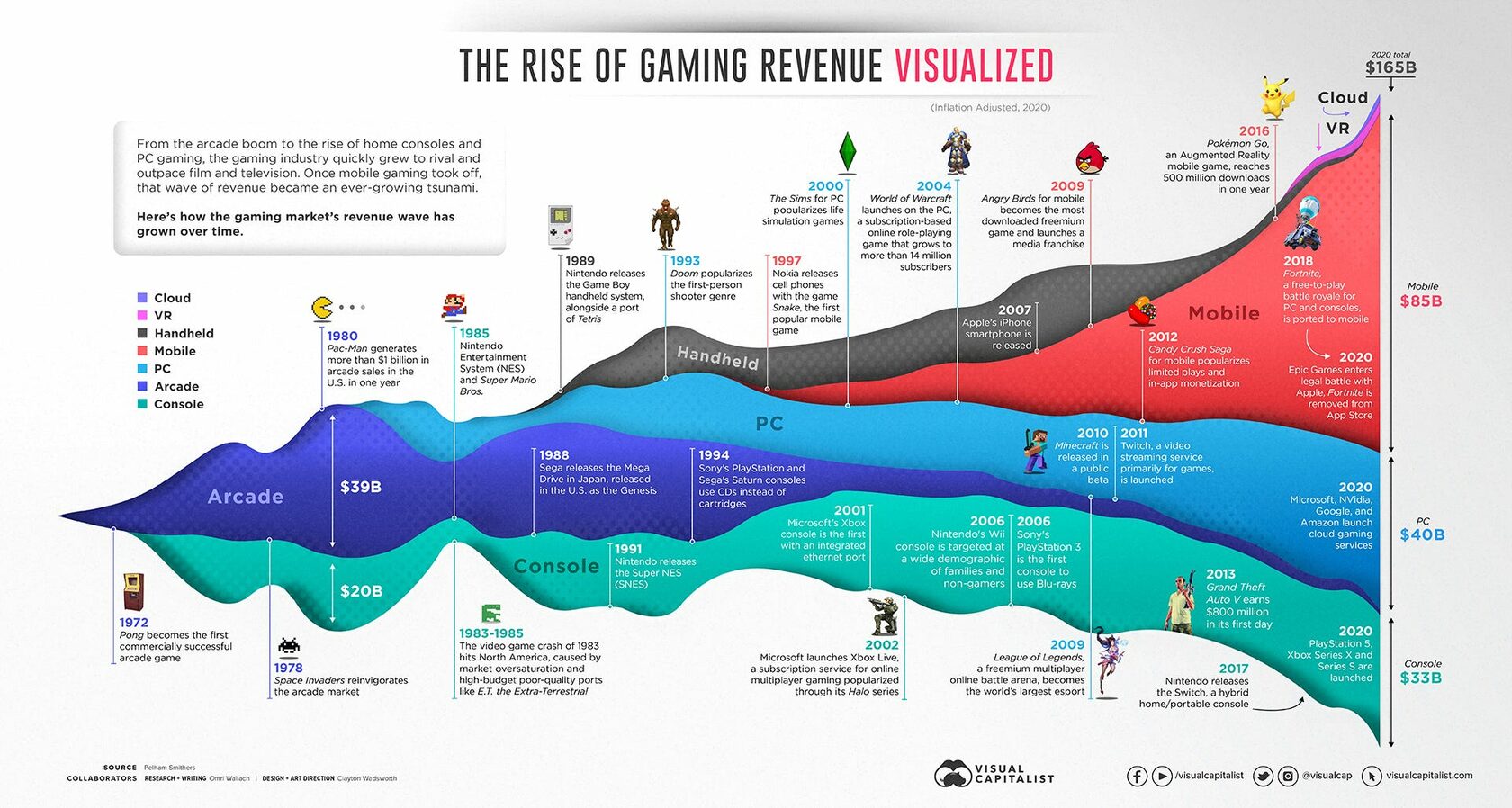

Figure 2. 50 years of video gaming revenue by revenue stream (1970-2020), according to Visual Capitalist.

What can go wrong – or: console games in 1983

In 1971, Nolan Bushnell, an employee from arcade manufacturer Nutting Associates, created Computer Space, the first purely electronic game to have a coin slot, marking the start of the video game industry. A year later, he would leave Nutting to found Atari, which initially focused on arcade development. Atari brought several innovations to the industry, and games like Pong were huge hits both in arcades and at home. The early successes paved the way for the launching in 1977 of Atari’s Video Computer System (VCS) 2600, the first commercially successful video game console.

At the time, the VCS 2600 was a technological marvel. Unlike prior generations of machines that used custom-built discrete circuits that allowed only a small number of games, it featured a complete CPU, and different games could be played by switching ROM cartridges which were sold separately. Thanks to company-developed games like Space Invaders, Missile Command and Combat, which were spectacular hits, VCS 2600 quickly became a hugely popular household electronic item, and by 1980, Atari commanded an 80% share of the video game market.

VCS 2600’s success, however, brought an unexpected problem: independent publishers. In a major engineering snafu, the VCS 2600 was designed without any guardrails protecting against third-party cartridges – anyone could engineer a ROM cartridge for it, provided it used the same connection standard, which was stupidly easy to reverse engineer.

Leveraging on this, by 1979, a team of distraught Atari programmers left to form their own company, Activision, and proceeded to develop their own games, becoming the first third-party company to release software for a video game console. Activision would go on to launch a few of the most successful ROM cartridges: Boxing, Kaboom!, River Raid, among several others – including Pitfall!, a major hit with over 4 million cartridges eventually being sold. A legal battle ensued between both companies, which was settled in 1982 (and which essentially made lawful for any other company to try to join the VCS ROM cartridge bonanza). By 1983, when Activision did its IPO, the company would register $157 million in revenues – worth about half a billion dollars today if we account for inflation –; not bad for a 3-year-old company in the pre-internet world.

Activision’s success paved the way for dozens of other independent developers, lured by the promise to spend a few dollars in a cartridge and selling them for several times that. While these new publishers should in theory pay royalties for Atari in exchange for a license to sell their games, the VCS 2600 had no built-in protection against unlicensed games, and the market was flooded with poor quality unlicensed games. Everyone and their mother decided they should create video game content, and ship it fast – Purina launched a game to sell dog food; there was a Kool-Aid Man video game; and then there was, of course, E.T. Based off of Steven Spielberg’s major movie hit, E.T. doubles as one of the worst games ever launched (play it here, if you dare) and as being the most expensive flop in the industry at that time.

In 1971, Nolan Bushnell, an employee from arcade manufacturer Nutting Associates, created Computer Space, the first purely electronic game to have a coin slot, marking the start of the video game industry. A year later, he would leave Nutting to found Atari, which initially focused on arcade development. Atari brought several innovations to the industry, and games like Pong were huge hits both in arcades and at home. The early successes paved the way for the launching in 1977 of Atari’s Video Computer System (VCS) 2600, the first commercially successful video game console.

At the time, the VCS 2600 was a technological marvel. Unlike prior generations of machines that used custom-built discrete circuits that allowed only a small number of games, it featured a complete CPU, and different games could be played by switching ROM cartridges which were sold separately. Thanks to company-developed games like Space Invaders, Missile Command and Combat, which were spectacular hits, VCS 2600 quickly became a hugely popular household electronic item, and by 1980, Atari commanded an 80% share of the video game market.

VCS 2600’s success, however, brought an unexpected problem: independent publishers. In a major engineering snafu, the VCS 2600 was designed without any guardrails protecting against third-party cartridges – anyone could engineer a ROM cartridge for it, provided it used the same connection standard, which was stupidly easy to reverse engineer.

Leveraging on this, by 1979, a team of distraught Atari programmers left to form their own company, Activision, and proceeded to develop their own games, becoming the first third-party company to release software for a video game console. Activision would go on to launch a few of the most successful ROM cartridges: Boxing, Kaboom!, River Raid, among several others – including Pitfall!, a major hit with over 4 million cartridges eventually being sold. A legal battle ensued between both companies, which was settled in 1982 (and which essentially made lawful for any other company to try to join the VCS ROM cartridge bonanza). By 1983, when Activision did its IPO, the company would register $157 million in revenues – worth about half a billion dollars today if we account for inflation –; not bad for a 3-year-old company in the pre-internet world.

Activision’s success paved the way for dozens of other independent developers, lured by the promise to spend a few dollars in a cartridge and selling them for several times that. While these new publishers should in theory pay royalties for Atari in exchange for a license to sell their games, the VCS 2600 had no built-in protection against unlicensed games, and the market was flooded with poor quality unlicensed games. Everyone and their mother decided they should create video game content, and ship it fast – Purina launched a game to sell dog food; there was a Kool-Aid Man video game; and then there was, of course, E.T. Based off of Steven Spielberg’s major movie hit, E.T. doubles as one of the worst games ever launched (play it here, if you dare) and as being the most expensive flop in the industry at that time.

Figure 3. Real posters of actual games launched for Atari VCS 2600 in 1983: “Kool-Aid Man” and Purina’s “Chase the Chuck Wagon”. What can go wrong?

The deluge of poor-quality content soon frustrated buyers, who became unwilling to buy more ROM cartridges. Resellers soon lowered prices to try to move product and froze purchase orders from developers, but the amount of poor-quality content was such that no one would be willing to have them, even for free. In a desperate attempt to resolve the issue, Atari buried the failed games in a landfill in New Mexico; something to the order of 700,000 cartridges were dumped there.

Less units of cartridges being sold, times lower price per cartridge, meant that the market was decimated. As a result, the US home video game market crashed – the industry lost 97% (not a typo, ninety-seven percent!) of its annual dollar sales volume between 1983 and 1985. Most independent publishers went bankrupt, and Atari would never return to video game stardom.

Less units of cartridges being sold, times lower price per cartridge, meant that the market was decimated. As a result, the US home video game market crashed – the industry lost 97% (not a typo, ninety-seven percent!) of its annual dollar sales volume between 1983 and 1985. Most independent publishers went bankrupt, and Atari would never return to video game stardom.

Figure 4. Picture taken in an 2014 excavation in the Atari video game dump in New Mexico. Original boxes of the games ET and Centipede are seen.

The video game console industry eventually came back through the emergence of Nintendo. Nintendo entered the U.S. market in 1985 with the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Again, as with Atari, the NES console was sold below or close to cost, while profits for Nintendo would come from cartridge sales. Learning from Atari’s troubles, however, Nintendo equipped each NES cartridge with an authentication chip, without which the game software could not connect to the console circuits.

No game could be published without Nintendo’s approval, and strict controls on the number of titles sold per developer were instituted; this allowed Nintendo to ensure royalties collection and product quality, creating the current standard business model for the video game console industry. To reinforce its profit formula, Nintendo built an exceptional in-house game development team, which produced hit games such as Super Mario Brothers (1985), The Legend of Zelda (1987), and Metroid (1987). By 1989, Nintendo controlled 90% of the home video game market, which was booming once again.

The moral of the story is simple: content curation is integral to the value of any creative asset. When the barriers for entry of creative products get lowered too fast, poor quality content floods an industry, and these will crowd out the good quality stuff. Value, then, shifts from the hands of the creators to the hands of the curators of content – a role which Nintendo learned well how to play. If there is no curation of content, such as the case with Atari, overall demand for the content can be expected to fall, even as the supply of content skyrockets. In this situation, excrement hits the rotating element fast.

What can go right – or: mobile games in 2008

Before 2005, essentially all video games were sold through brick-and-mortar stores as physical copies (cartridges, floppy disks, CDs/DVDs, as the case may be), with high production and distribution costs associated with them. By 2005, Valve opened up its online video game distribution service, Steam, for use by third-party publishers, which slowly began enrolling in it to sell and deliver PC games via the internet. By July 2008, there were over 350 games available on Steam for purchase, and its user base exceeded 10 million accounts.

While this was an amazing story per se, it was limited to PC gaming, so it was only a harbinger of the things to come; enter the iPhone, the App Store, and the smartphone revolution it engendered. The App Store greatly simplified the work of developers, as it standardized the libraries and environment they need to work in in order to build applications for a mobile device, and also provided them with a single, curated channel to deliver their apps to the end user (for those interested, the event where Steve Jobs introduces the App Store is an amazing historical piece).

The unprecedented success of the iPhone and its several versions was followed in tandem by the also-unprecedented success of the App Store: by July 2008, when the iPhone’s App Store was launched, it had just 500 applications available for download; by 2021, that number skyrocketed to over 4.4 million apps, with games representing the largest app category. A similar explosion happened in Android via its Android Market (first name of Google Play Store), which was launched in October 2008. History would see smartphones becoming ubiquitous worldwide, and by 2023, there were over 4 billion smartphone users worldwide.

Now imagine you’re an observer of the video game industry in 2008. You’re thinking about the future of the industry as you see developers around you selling games for a meager $1 per download – or, worse still, for free. You could certainly argue you’re witnessing the 1983 crash happening all over again, right?

You certainly could, and some good people did think that. But you’d be dead wrong, of course, as you’d be missing the point.

As smartphones penetrated nearly every demographic, mobile games could reach an extensive range of users, broadening the market and eliminating the need for gamers to spend any money at all on video game consoles. As such, mobile games' affordability and accessibility attracted new gamers, many of whom had never played video games before. People started playing games in their commutes, while waiting in line, or even in bathroom breaks. New game genres and better mobile UX evolved to suit the constraints of this new type of gamer: casual gaming (Candy Crush Saga), simulation (The Sims), unique sports experiences (Tennis Clash), among countless others came about.

In stark opposition to 1983, the advent of the App Store led to distribution costs being a tax on revenues (that is, the famous 30% that goes to Apple) instead of being a cash cost item per unit of inventory. Finally, the mobile gaming industry also learned from Atari’s story as Apple played the role of content curator quite well (maybe even too well, as any mobile game developer will tell you). Steve Jobs himself believed in the importance of that role for Apple; he himself said, when announcing the App Store: “Will there be limitations? Of course; there are going to be some apps that we are not going to distribute.”

No game could be published without Nintendo’s approval, and strict controls on the number of titles sold per developer were instituted; this allowed Nintendo to ensure royalties collection and product quality, creating the current standard business model for the video game console industry. To reinforce its profit formula, Nintendo built an exceptional in-house game development team, which produced hit games such as Super Mario Brothers (1985), The Legend of Zelda (1987), and Metroid (1987). By 1989, Nintendo controlled 90% of the home video game market, which was booming once again.

The moral of the story is simple: content curation is integral to the value of any creative asset. When the barriers for entry of creative products get lowered too fast, poor quality content floods an industry, and these will crowd out the good quality stuff. Value, then, shifts from the hands of the creators to the hands of the curators of content – a role which Nintendo learned well how to play. If there is no curation of content, such as the case with Atari, overall demand for the content can be expected to fall, even as the supply of content skyrockets. In this situation, excrement hits the rotating element fast.

What can go right – or: mobile games in 2008

Before 2005, essentially all video games were sold through brick-and-mortar stores as physical copies (cartridges, floppy disks, CDs/DVDs, as the case may be), with high production and distribution costs associated with them. By 2005, Valve opened up its online video game distribution service, Steam, for use by third-party publishers, which slowly began enrolling in it to sell and deliver PC games via the internet. By July 2008, there were over 350 games available on Steam for purchase, and its user base exceeded 10 million accounts.

While this was an amazing story per se, it was limited to PC gaming, so it was only a harbinger of the things to come; enter the iPhone, the App Store, and the smartphone revolution it engendered. The App Store greatly simplified the work of developers, as it standardized the libraries and environment they need to work in in order to build applications for a mobile device, and also provided them with a single, curated channel to deliver their apps to the end user (for those interested, the event where Steve Jobs introduces the App Store is an amazing historical piece).

The unprecedented success of the iPhone and its several versions was followed in tandem by the also-unprecedented success of the App Store: by July 2008, when the iPhone’s App Store was launched, it had just 500 applications available for download; by 2021, that number skyrocketed to over 4.4 million apps, with games representing the largest app category. A similar explosion happened in Android via its Android Market (first name of Google Play Store), which was launched in October 2008. History would see smartphones becoming ubiquitous worldwide, and by 2023, there were over 4 billion smartphone users worldwide.

Now imagine you’re an observer of the video game industry in 2008. You’re thinking about the future of the industry as you see developers around you selling games for a meager $1 per download – or, worse still, for free. You could certainly argue you’re witnessing the 1983 crash happening all over again, right?

You certainly could, and some good people did think that. But you’d be dead wrong, of course, as you’d be missing the point.

As smartphones penetrated nearly every demographic, mobile games could reach an extensive range of users, broadening the market and eliminating the need for gamers to spend any money at all on video game consoles. As such, mobile games' affordability and accessibility attracted new gamers, many of whom had never played video games before. People started playing games in their commutes, while waiting in line, or even in bathroom breaks. New game genres and better mobile UX evolved to suit the constraints of this new type of gamer: casual gaming (Candy Crush Saga), simulation (The Sims), unique sports experiences (Tennis Clash), among countless others came about.

In stark opposition to 1983, the advent of the App Store led to distribution costs being a tax on revenues (that is, the famous 30% that goes to Apple) instead of being a cash cost item per unit of inventory. Finally, the mobile gaming industry also learned from Atari’s story as Apple played the role of content curator quite well (maybe even too well, as any mobile game developer will tell you). Steve Jobs himself believed in the importance of that role for Apple; he himself said, when announcing the App Store: “Will there be limitations? Of course; there are going to be some apps that we are not going to distribute.”

Figure 5. Email of Steve Jobs responding to a developer that complained about Apple’s curation process in the early days of the App Store.

New potential gamers, coupled with this new distribution cost paradigm and Apple's curation of the App Store, empowered developers to succeed in radically new business models, eventually leading to the rise of the freemium model – with big games such as Game of War, Sniper 3D, Fortnite and Pokémon Go eventually being offered for zero dollars for anyone willing to play the game. The world found out that a winning formula in the gaming industry was a model that allowed for the full price discrimination of gamers. Pokémon Go alone, for example, generated over $6 billion in revenue since its release in July 2016, according to Sensor Tower.

Newzoo estimates that the global video game market reached $197 billion in 2022, with mobile games accounting for $104 billion, or 53% of the total market revenue – a segment of the market which essentially did not exist until late 2008. What’s more, the mobile gaming market grew mostly from non-consumption and did not seem to cannibalize the growth from other parts of the industry, such as PC or console gaming. That’s quite a happy ending.

And now for the moral of the mobile gaming story. While quality of the content is always going to be important, it should matter more to discover if the content being generated will be consumed by more people, in circumstances where content consumption would usually not happen, and/or through different means of consumption. If this is the case, then the total value of the market should increase, with the new type of content being produced earning the lion’s share of market growth.

Wrapping it up

It’s not at all clear if AI-generated content is a story closer to console gaming in 1983, or to mobile gaming in 2008. In any case, the fundamentals that make betting on blockbusters the winning strategy in content generation may have changed, and this should bring a tectonic shift in the market value of content industries.

In one extreme, we may be witnessing the dawn of an age where even big screen actors are made obsolete by AI, where quality content gets crowded out due to poor curation of content and any and the entertainment industry as a whole comes crashing down. Should that be the case, then the value of creating content would plunge, and value should concentrate in the hands of the content curators, who would sell the service of separating wheat from chaff.

In another extreme, we may see an explosion of value in the entertainment industry as AI gets introduced as a source of content, making traditional workflows much cheaper and simpler (as in the Corridor Crew’s anime), thus pricing in creators that would otherwise never be able to join the market.

We stick with what we said about a month ago:

The only thing that’s certain is that, however creative we may be, we will never be able to anticipate nth-order effects that will come as a consequence of the events we are partaking in today. The next few years will be weird, and we’ll see the emergence of at least one completely new, revolutionary sector that will generate multi-trillion-dollar wealth – a sector we could never predict today, however clear our crystal ball could be.

Indeed, by the time we wrote that article (March 13):

…and, of course, we would not have anticipated all these things happening within the span of 36 days.

The best is yet to come. Onward!

Newzoo estimates that the global video game market reached $197 billion in 2022, with mobile games accounting for $104 billion, or 53% of the total market revenue – a segment of the market which essentially did not exist until late 2008. What’s more, the mobile gaming market grew mostly from non-consumption and did not seem to cannibalize the growth from other parts of the industry, such as PC or console gaming. That’s quite a happy ending.

And now for the moral of the mobile gaming story. While quality of the content is always going to be important, it should matter more to discover if the content being generated will be consumed by more people, in circumstances where content consumption would usually not happen, and/or through different means of consumption. If this is the case, then the total value of the market should increase, with the new type of content being produced earning the lion’s share of market growth.

Wrapping it up

It’s not at all clear if AI-generated content is a story closer to console gaming in 1983, or to mobile gaming in 2008. In any case, the fundamentals that make betting on blockbusters the winning strategy in content generation may have changed, and this should bring a tectonic shift in the market value of content industries.

In one extreme, we may be witnessing the dawn of an age where even big screen actors are made obsolete by AI, where quality content gets crowded out due to poor curation of content and any and the entertainment industry as a whole comes crashing down. Should that be the case, then the value of creating content would plunge, and value should concentrate in the hands of the content curators, who would sell the service of separating wheat from chaff.

In another extreme, we may see an explosion of value in the entertainment industry as AI gets introduced as a source of content, making traditional workflows much cheaper and simpler (as in the Corridor Crew’s anime), thus pricing in creators that would otherwise never be able to join the market.

We stick with what we said about a month ago:

The only thing that’s certain is that, however creative we may be, we will never be able to anticipate nth-order effects that will come as a consequence of the events we are partaking in today. The next few years will be weird, and we’ll see the emergence of at least one completely new, revolutionary sector that will generate multi-trillion-dollar wealth – a sector we could never predict today, however clear our crystal ball could be.

Indeed, by the time we wrote that article (March 13):

- Stable Diffusion XL wasn’t a thing, and neither was Midjourney v5.

- Bing Chat still had a waitlist, and Bing Images was not a generative AI.

- Google Bard had not been launched yet.

- We did not have GPT4, let alone GPT4 plugins.

- LangChain did not exist.

- No one knew you could quantize LLaMa to 4-bits with minimal loss of quality, and even run it in the CPU achieving several tokens/second in consumer-grade machines.

- No one thought we could instruction-train small LLMs to make them behave like ChatGPT. Stanford’s Alpaca paper had not even been published, let alone Vicuña, GPT4All or OpenAssistant.

- We didn’t have yet a music collaboration between The Weeknd and Drake that was entirely made up — from lyrics to beats to harmony and voice, the song was all was made up by AI.

- Naturally, no one spoke of autonomous agents such as AutoGPT or BabyAGI.

…and, of course, we would not have anticipated all these things happening within the span of 36 days.

The best is yet to come. Onward!